Pixel vs. Texel

Digital images are composed of dots arranged on a grid. Each of these little dots is called a pixel, a contraction of the term 'picture element'. The same is true of the texture graphics that get drawn onto polygons in 3D games; a Texel simply a pixel within a texture image.

Pixel is the fundamental unit of screen space.

Texel, or texture element (also texture pixel) is the fundamental unit of texture space.

Textures are represented by arrays of Texels, just as pictures are represented by arrays of pixels. When texturing a 3D surface (a process known as texture mapping) the renderer maps Texels to appropriate pixels in the output picture.

Between, it is more common to use fill rate instead of write speed and you can easily find all required information, since this terminology is quite old and widely-used.

As part of their performance specifications, graphics cards often describe how many Texels they can process each second. This is their texture fill rate: the number of times a GPU can access a texture in a single second.

To access a texture, one often employs filtering. This is a way to fill in the gaps "between" Texels, so that you do not have easily visible edges between Texels.

All fill-rate numbers are expressed in Megapixels/sec or Mega Texels/sec. Well, the original idea behind fill-rate was the number of finished pixels written to the frame buffer. So in the good old days it made sense to express that number in Megapixels. However, with the second generation of 3D accelerators a new feature was added. This feature allows you to render to an off screen surface and to use that as a texture in the next frame. So the values written to the buffer are not necessarily on screen pixels anymore, they might be Texels of a texture. This process allows several cool special effects, imagine rendering a room, now you store this picture of a room as a texture. Now you don't show this picture of the room but you use the picture as a texture for a mirror or even a reflection map, Another reason to use MegaTexels is that games are starting to use several layers of multi-texture effects, this means that a on-screen pixel is constructed from various sub-pixels that end up being blended together to form the final pixel. So it makes more sense to express the fill-rate in terms of these sub-results, and you could refer to them as Texels.

One of the biggest differences between Texels and pixels is that pixels are image data. Texels do not have to be.

In modern shader-based rendering systems, textures, and thus their component texels, are arbitrary data. They have only what meaning the shader gives them. They certainly can be an image, but they can also be a lookup table. Or a depth map that tells where to start shadows. Or Fresnel table for computing Cook-Torrance specular reflectance.

Resolution for both pixels and Texels have been growing. Until the 6th generation, most video game systems were stuck with screen resolutions about half of standard. A standard TV set has a resolution of 640×480 pixels, and those game systems had a resolution of 320×240 or less. With 2D systems, this was a happy marriage of saving expensive console memory in the frame buffer and saving ROM space, as high resolution sprites take up a lot of ROM size. With 3D systems, this was to save memory, as frame buffers were small at the time. The Nintendo 64 could go to full standard with a memory upgrade, but even then the pixel fill rate prevented it from running smoothly on many games. Staying at 320×240 also saved performance, as rendering at 640×480 took four times as long on the fill rate-limited renderers of the day than 320x240.

The 6th generation brought 640×480, as well as a lot more video memory for bigger textures. On the Xbox, low-complexity scenes could even show at 720p resolution (1280×720).Now we have high definition systems, which offer both high screen resolutions and high texture resolutions. The latter is important, as PC games could do high screen resolutions for years, but with standard resolution textures, that was just "up scaling"; the methods of shader post-processing to hide the blur of upscale textures often looked artificial.

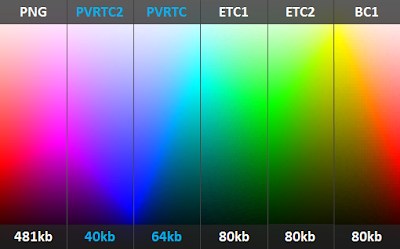

With the more modern GPUs on PlayStation 3 and the Xbox 360, texture resolutions have been extremely high, but screen resolutions have sometimes been actually lower than the accepted HD minimum of 720 pixels high. This is primarily due to the rise in programmability in GPUs. Executing a complex program can take quite a long time; complex programs also use more textures to do specialized effects. Lighting, proper shadow, in short, all of the things we accept in modern graphics-intensive games, have a cost to them. And that cost comes primarily out of the pixel fill rate. Reducing the overall pixel count means less work for the frame buffer, with the same performance. As for fitting all the texture resolution, that's partly thanks to memory, and partly thanks to Texture Compression.

Comments

Post a Comment